Parking laboratory

what did we learn from the process so far?

the challenge

How can we rethink the parking system in the Izgrev to achieve cleaner air by involving citizens in the process?

How can parking areas be expanded and upgraded to reduce traffic and improve air quality?

What kind of parking system would balance the environmental, social, and economic interests of all stakeholders?

How can citizens be at the center of new policymaking?

We sought answers to these and other questions in the “Parking Lab” process, which aims to test a new type of interaction between local administration and stakeholders in the development and implementation of policies related to urban mobility and air quality.

“Parking Lab” was led by Chaordika association with teams from Open Space collective and Hype communications, and in collaboration with “Izgrev” district in Sofia. It is part of the global Breathe Cities program – a first-of-its-kind initiative of the Clean Air Fund, C40 Cities and Bloomberg Philanthropies, which aims to improve air quality, reduce carbon emissions and contribute to better public health in cities around the world.

In the following lines, we share key lessons learned and recommendations from the process.

the approach

To rethink the parking system and the existing models of interaction with stakeholders, we applied an experimental and social approach, based on the methodology of the Social Innovation Labs.

In the “Parking Lab”, representatives from various sectors developed new solutions through dialogue, created prototypes, and tested them in a real-world environment to identify what brings about the desired change.

-

usually...

How do we define the problem?

Unilaterally and by experts only

Whom do we include?

There is no stakeholder analysis, or it is done formally

When do we engage citizens?

Once a solution has already been developed by experts

What is discussed?

For/against a given solution. Opposing camps and polarisation are created.

How is feedback gathered?

Online surveys or a single public discussion.

-

THe lab approach

How do we define the problem?

By involving all affected parties, who participate in defining the problem even before discussing how to solve it.

Whom do we involve?

Mapping is part of the engagement process and is done via meetings and discussions.

The invitation is a well-planned and proactive process.

A community of diverse participants is created, which meets and works together on a given problem over a long period of time.

When do we involve citizens?

At the earliest stage, before the experts develop the solution. As many perspectives and aspects as possible are collected, which are used in the expert decision-making process.

What is discussed?

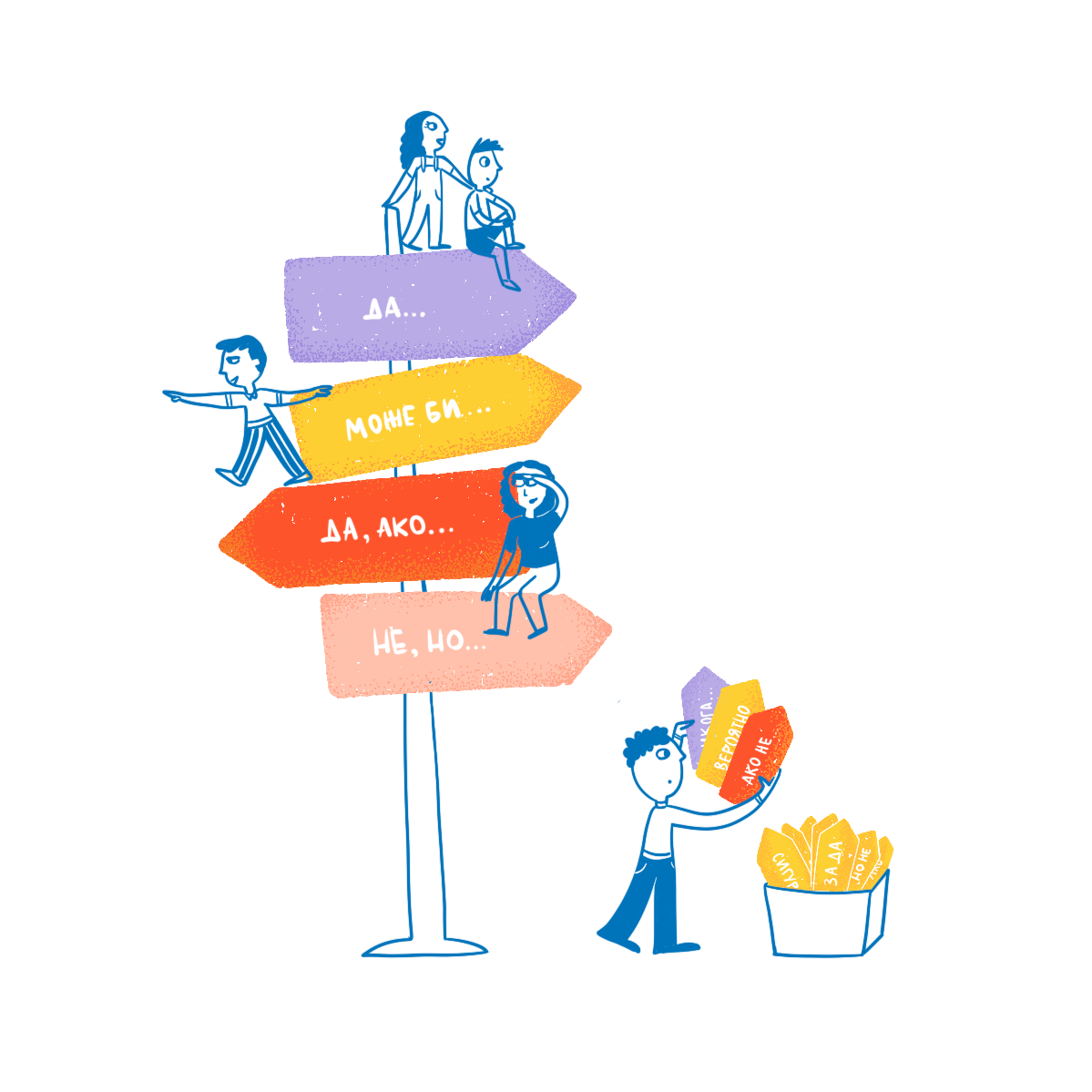

Different options and nuances of possible solutions, opening up new opportunities for common ground between different opinions and interests

How is feedback gathered?

A combination of different approaches - online, face-to-face, experimentation with formats and locations - workshops, information presentations, interviews, physical interventions, and surveys.

the process

phase 1: exploring the topic and forming an active group

In this stage, we worked on several levels - on the one hand, reviewing documents and existing parking regimes in the Izgrev district, and on the other hand, mapping the widest possible range of stakeholders to be involved in the exploration of the challenges through their experience and experiences.

Our goal from the very beginning of the process was to engage interested groups in a dialogue about possible solutions beyond the paid zones as the only solution, and to explore the topic in the broader context of the relationship between the quality of life in neighborhoods and the predominant car mobility.

In this stage, we held:

A first open citizens meeting to explore attitudes towards participation in such a process and to identify the main challenges;

A meeting with representatives of schools, kindergartens, and community centers in the area;

Individual meetings with business representatives;

A meeting with representatives of the district administration;

A meeting with representatives of the Center for Urban Mobility;

An online survey to investigate parking issues in the area, which we distributed online and physically via QR codes in neighborhoods.

As a result, we identified the main parking issues in the area, a list of specific locations that were identified as the most problematic, and created a channel for communication with representatives of various groups who expressed a desire to be part of the process in various forms.

Phase 2: POssible solutions

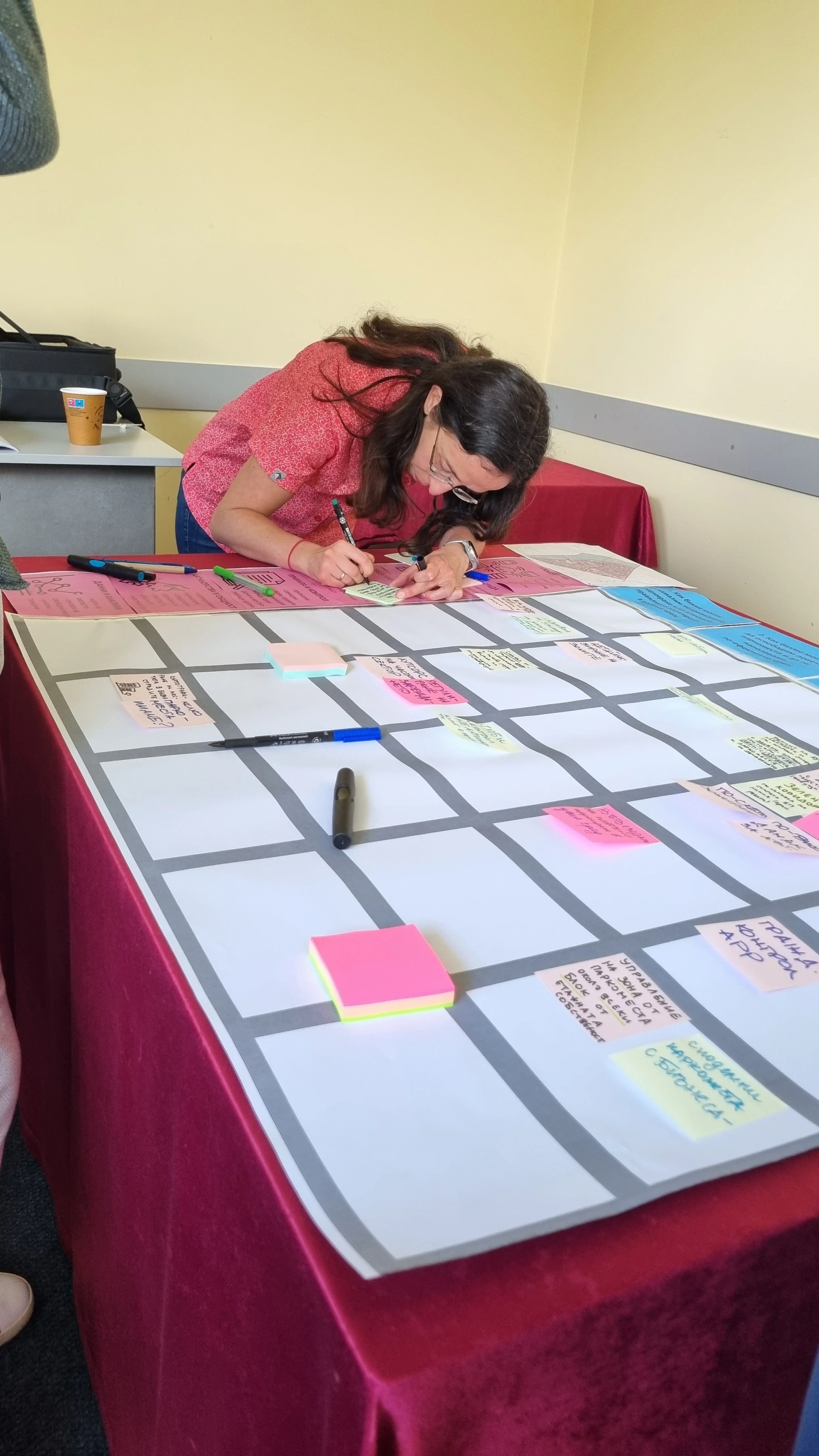

In this step, we focused on the joint creation of possible solutions and scenarios.

We held a public meeting, in which we validated the problems identified in the survey and held an initial discussion about possible solutions. The discussion contributed to expanding the group of active citizens and the first contact was made with active representatives of the homeowners. Subsequently, we organized a closed meeting with a larger group of representatives of the homeowners, which showed us the great untapped potential of working with this group. The participants in the meeting themselves realized that they could work together in the future on other topics and created a group for communication between them.

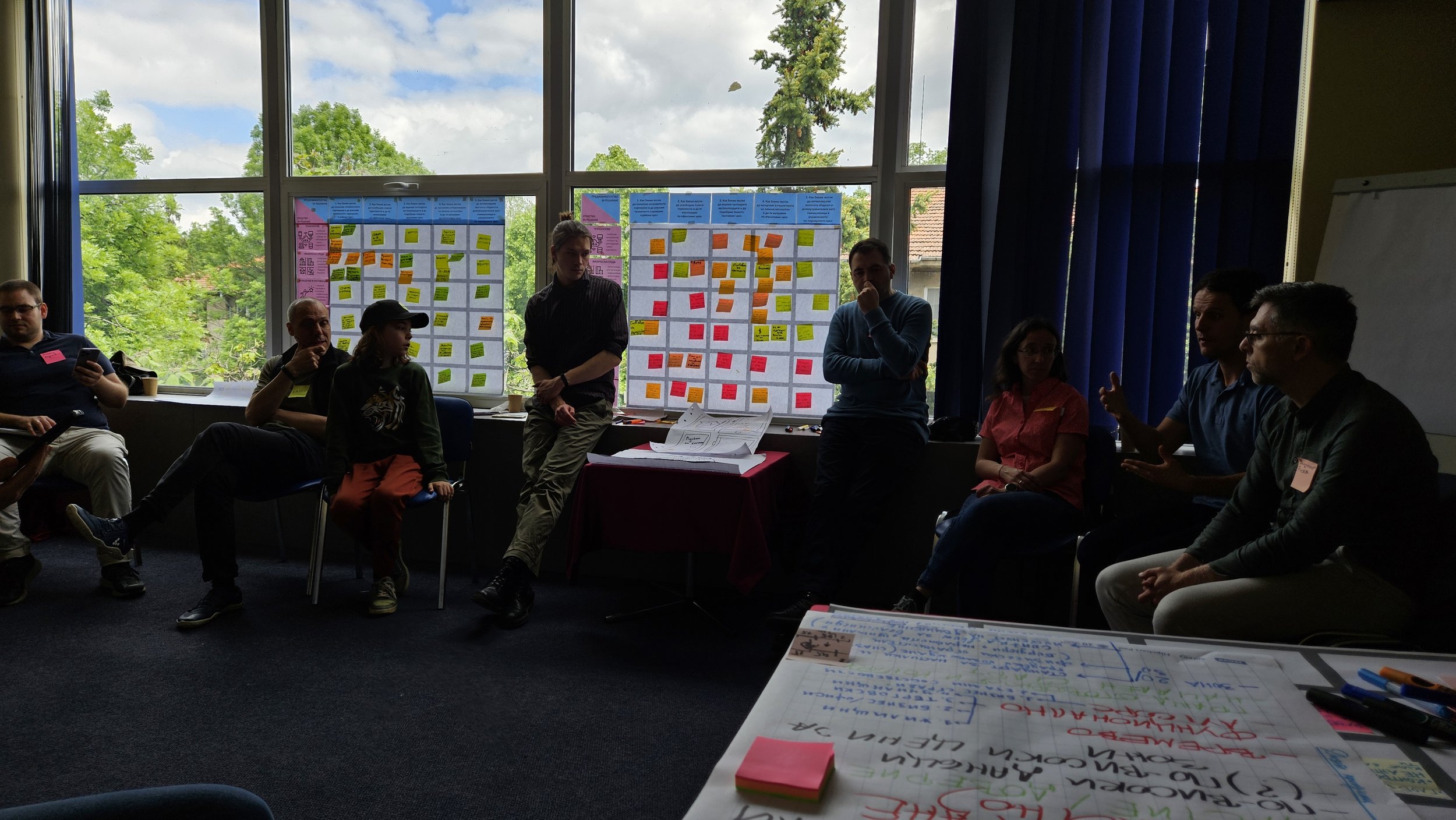

At this stage, we also included experts - specifically urban planners, designers, and transport engineers, who participated in a workshop to prepare solution scenarios together with citizens and representatives of the administration.

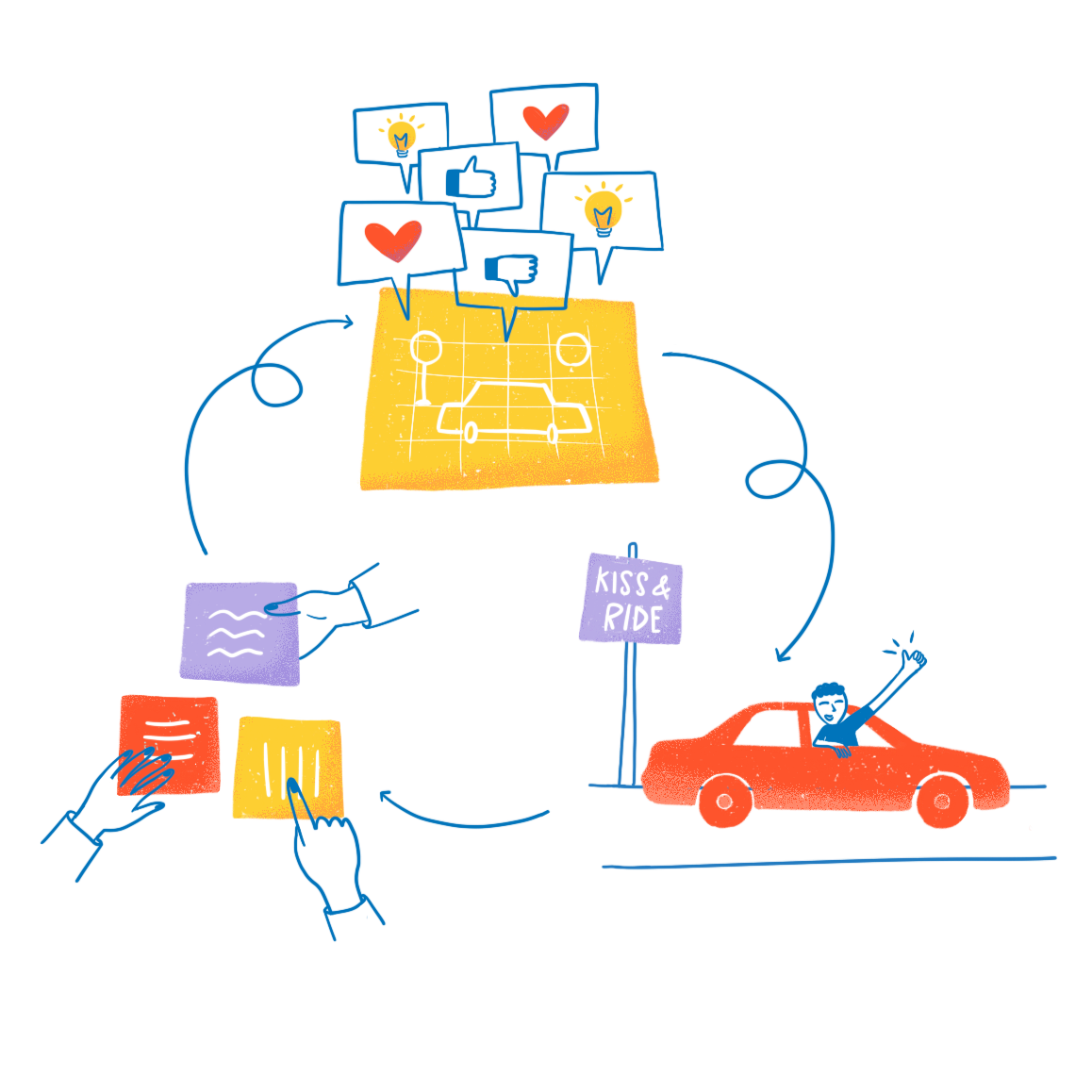

Some of the proposed solutions included testing a Kiss and Ride zone around a school, exploring the possibilities for creating functional subzones, as well as the improvement of the so-called “mud points”.

We then conducted an online survey to validate the proposed solutions, their applicability, and possible impact, through which additional feedback was collected. At this stage, we also conducted a representative sociological survey that explored attitudes towards parking problems, as well as some possible solutions.

phase 3: prototyping

In the social innovation lab approach, learning and solution creation occur through dialogue, but also through small concrete steps, through which we check in a real environment whether the idea for a given solution would really have a good effect and how it would be perceived by the stakeholders.

Prototypes are low-risk and low-budget interventions, with which we demonstrate for a short period of time what a solution would look like and test what would work well and what to change.

At the Parking Lab, we tested a prototype of a “Kiss and Ride” zone around the German School, which citizens suggested to demonstrate the possibility of creating functional subzones around schools. The hypothesis of the prototype was that introducing such a zone would strategically increase the turnover of stopping cars, which in turn would reduce dwell time and the negative impact on the environment and safety around the school.

Additionally, we explored the topic of the so-called “mud spots” - places in the area that are designated for landscaping, but are in practice used as parking lots. We conducted a short survey among active citizens of the area, who identified such places with potential for improvement, and we held an information session on the tactical urbanism (a.k.a. placemaking approach). The information and knowledge gathered is a good basis for future initiatives by the administration in the area.

mix of methodologies and approaches

In the Parking Lab process, we combined different methodologies to explore problems and create solutions. The combination of individual interviews, group workshops, personal story exploration, along with data analysis and conducting questionnaires and a sociological survey, as well as the implementation of a prototype, allowed us to gain a more holistic view of the complex problem and possible solutions.

interactive discussions and workshops

Unlike traditional consultations, the meetings we organized were designed and facilitated in a way to allow participants to express their opinions in a constructive way and contribute to the co-creation of solutions. Through these meetings, we not only reached aspects that research or experiments alone could not provide, but also created the foundations for building trust and a community of active citizens in the area.

Types of meetings we organised:

Individual dialogic interviews;

Meetings with specific groups of stakeholders (district administration, representatives of homeowners in the area, representatives of cultural and educational institutions, owners of small and medium-sized businesses in the area);

Open meetings with all interested citizens;

Workshops with representatives of various stakeholders, experts and representatives of the district administration;

Online information session on the tactical urbanism (Placemaking) approach and how it can be applied to the “mud spots” in the Izgrev area;

A working meeting with the local authorities to present the data from the sociological survey and the results of the project, as well as a discussion on the possibilities for more active involvement of citizens in the development of local policies.

Recommendations for organising open meetings with stakeholders

Meeting Design: Before preparing the invitation for the event, think carefully about the purpose of the meeting and the methods you will use to stimulate constructive participation. Prepare materials that you will present (data, presentations, proposals) and draw up an agenda.

Invitation: Create an invitation that reflects the purpose of the meeting. Include a brief description of the goals, agenda, location, and time of the meeting. Distribute the invitation through various channels such as social networks and active citizen groups, as well as in frequently visited places - community centers, the municipality building, cafes, shops, etc.

Participants: The best discussions happen when we reach the widest possible circle of citizens, including usually underrepresented groups. Think about how to make the event accessible to people with mobility challenges or parents with children.

Place and time: Choose a place in the area that is well-known and easily accessible by public transport and car, as well as for people with mobility issues. Ideally, the room should allow for small group discussions. Choose a time after working hours or on weekends.

Facilitation: Make sure you have an experienced facilitator to lead the meeting. Ideally, this is someone neutral who can handle conflict if it arises.

Next steps: Engagement processes are not one-off meetings. So make sure you inform participants of the next steps and have their contact information so you can stay in touch.

2. questionnaires and a sociological survey

In the process, we conducted two online questionnaires and one representative survey. In the first questionnaire, we explored the roots of the parking problems in the area and collected information about the most problematic places. Over 150 people participated in it.

In the second questionnaire, we presented the ideas for solutions jointly created in the process, with the idea of validating and prioritizing them. Over 100 people participated in it. Through these surveys, we were also able to collect information about the most problematic areas in the area, as well as about the “muddy spots” that could be improved.

The surveys were not representative in nature and were distributed among the participants in the meetings, groups of active citizens, as well as through posters with QR codes in public places in the area.

By conducting the representative sociological study, we wanted to achieve several goals:

To validate the public attitudes towards some of the solutions for organizing the parking system, which we reached in the collective process;

To strengthen our understanding of how citizens interact with local government on the topic and how these processes can be improved.

3. Prototyping

Alongside discussion formats, one of the most impactful ways to engage citizens is to invite them to participate in the planning and implementation of a specific physical intervention that would improve the environment around them. This can be through approaches like tactical urbanism or Placemaking, which involve the local community not only in the implementation, but also in the planning and design of urban spaces, or through temporary interventions to test possible solutions (prototyping).

The added value of such engagement approaches lies in the possibility of attracting groups of citizens who are less likely to engage in discussions and public deliberations, as well as the potential to collect feedback in a real-world environment and refine concepts for possible future changes at an early stage.

the prototyping process

You can see the results of the sociological survey below.

-

At the beginning and end of the school day, the area in front of the German School in Sofia is subject to serious traffic congestion, as are many other schools in the capital. This leads to several negative consequences:

Air pollution due to running engines and traffic jams.

Increased risk to students' road safety.

General chaos and traffic jams affecting the entire neighborhood.

-

The hypothesis of the prototype was that introducing a “Kiss and Ride” zone would strategically increase the turnover of stopping cars, which in turn would reduce dwell time and the negative impact on the environment and safety around the school.

-

The idea was proposed by citizens at one of the practical workshops and in the process we continued to actively involve various groups through:

A survey conducted among 74 parents.

In-depth interviews with 10 parents.

Discussion with the student council to take into account the perspective of the children themselves.

-

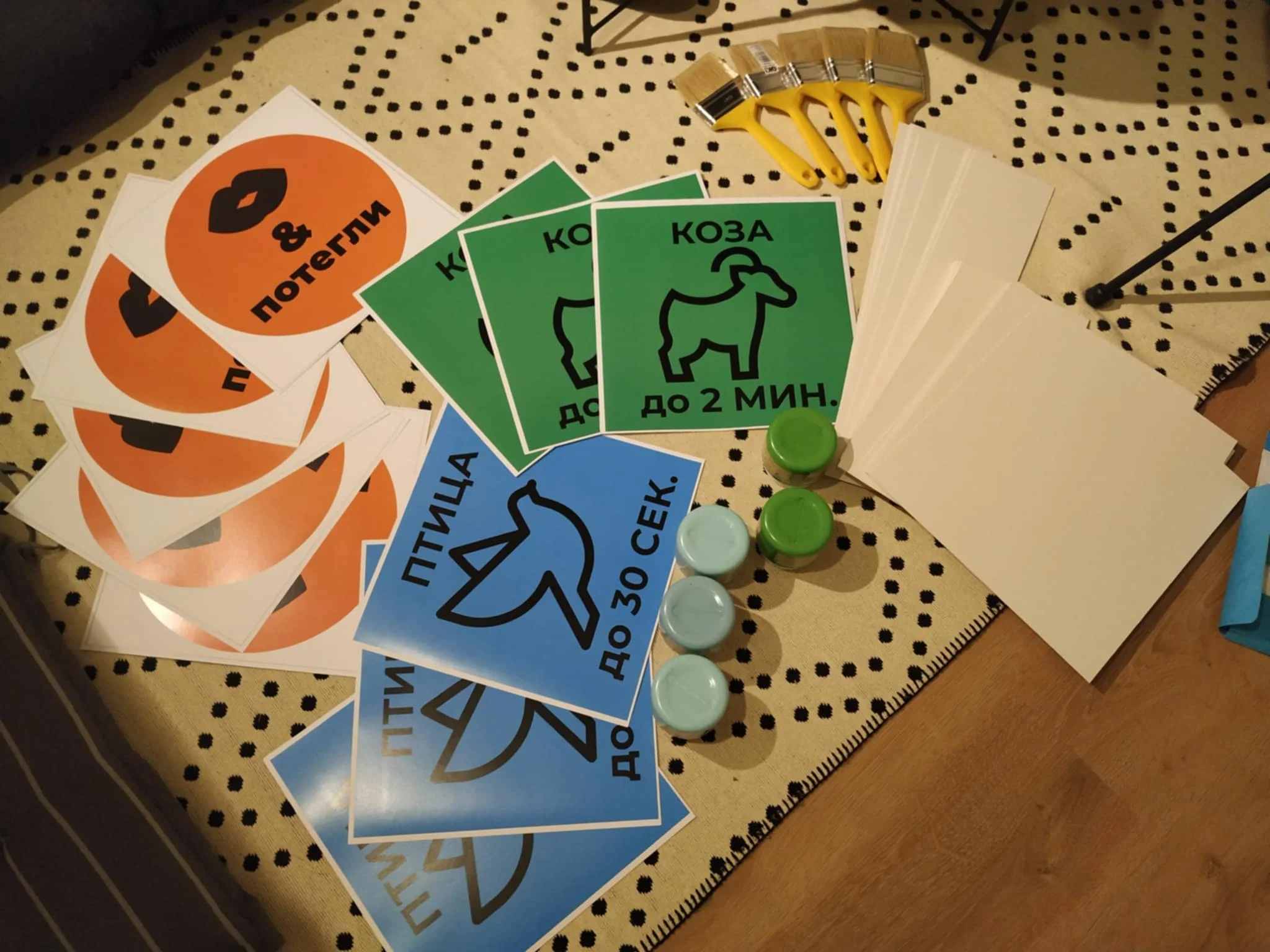

Within the prototype, a total of 5 short-term parking spaces have been allocated, distributed according to the length of stay:

2 parking spaces with a stay limit of up to 30 seconds.

3 parking spaces with a stay limit of up to 2 minutes.

-

Over the course of a week, parents who volunteered to take part in the test put stickers on their cars and stopped at designated locations, trying to meet the time limits. Volunteers, including students, observed the process and noted opportunities for improvement.

-

At the end of the process, an analysis of the effectiveness of the zone is to be carried out, which includes:

Measuring the turnover of parking spaces (how often cars change).

Monitoring strict compliance with time restrictions.

Observing the attitude and behavior of both parents and children towards the new organization via conversations and through a survey.

Some lessons learned from the prototyping

The one-week prototype demonstrated the feasibility of implementing a short-term parking system and its potential to improve safety and traffic management around schools. In addition to the positive impact on parking management, unexpected positive effects were also observed during the test period. For example, some parents choose to walk or use the metro when picking up their children during the test week. This also shows the potential for long-term behavioral changes.

Based on the analysis of the first results of the prototype “Kiss & Ride” zone at the German School in Sofia, we can summarize several key lessons learned that will help us improve the concept:

Institutional framework and regulations

Bulgaria lacks a flexible procedure for temporary testing of innovations in urban environments. The lack of a so-called “sandbox” approach (protected experimental environment) hinders learning through real-world testing. There is a need to create a flexible regulation or pilot procedure for experimental testing of innovative solutions.

Engagement and communication

Preparation and engagement start well before the physical test. Standard methods of communicaiton such as emails and posters are usually not sufficient. Multi-level communication, including personal contact, field presence, and reminders, is needed. Involving parents, students, and school management in the design, preparation, and implementation is key to the success of the prototype.

Prototype design and habits

Combining too many changes at once (location, direction of movement, and new rules) is not effective. Prototypes should build on existing behaviour and introduce only one major change at a time.

Participant engagement

“Early adopters” versus the majority: highly motivated parents are important for the start, but a voluntary model is not enough for mass engagement. When the majority does not participate, it demotivates even active participants. To influence “conservative” citizens, formal regulation and institutional support are needed, not just school rules.

what did we learn about the parking issue in izgrev district?

The topic touches on many systemic issues - including those related to the culture of car ownership, the use of public spaces and the rapid urban development in older neighborhoods. Usually, the conversation on the topic is largely limited to the discussion "for" or "against" the introduction of a paid parking zone. In the process of interaction with citizens and other stakeholders, we found that the introduction of a paid zone could be a solution to some of the problems, but for the rest there is a need for a conversation about the specific needs of the area and in the specific neighborhoods.

Key recommendations

recommendations for better citizens engagement

-

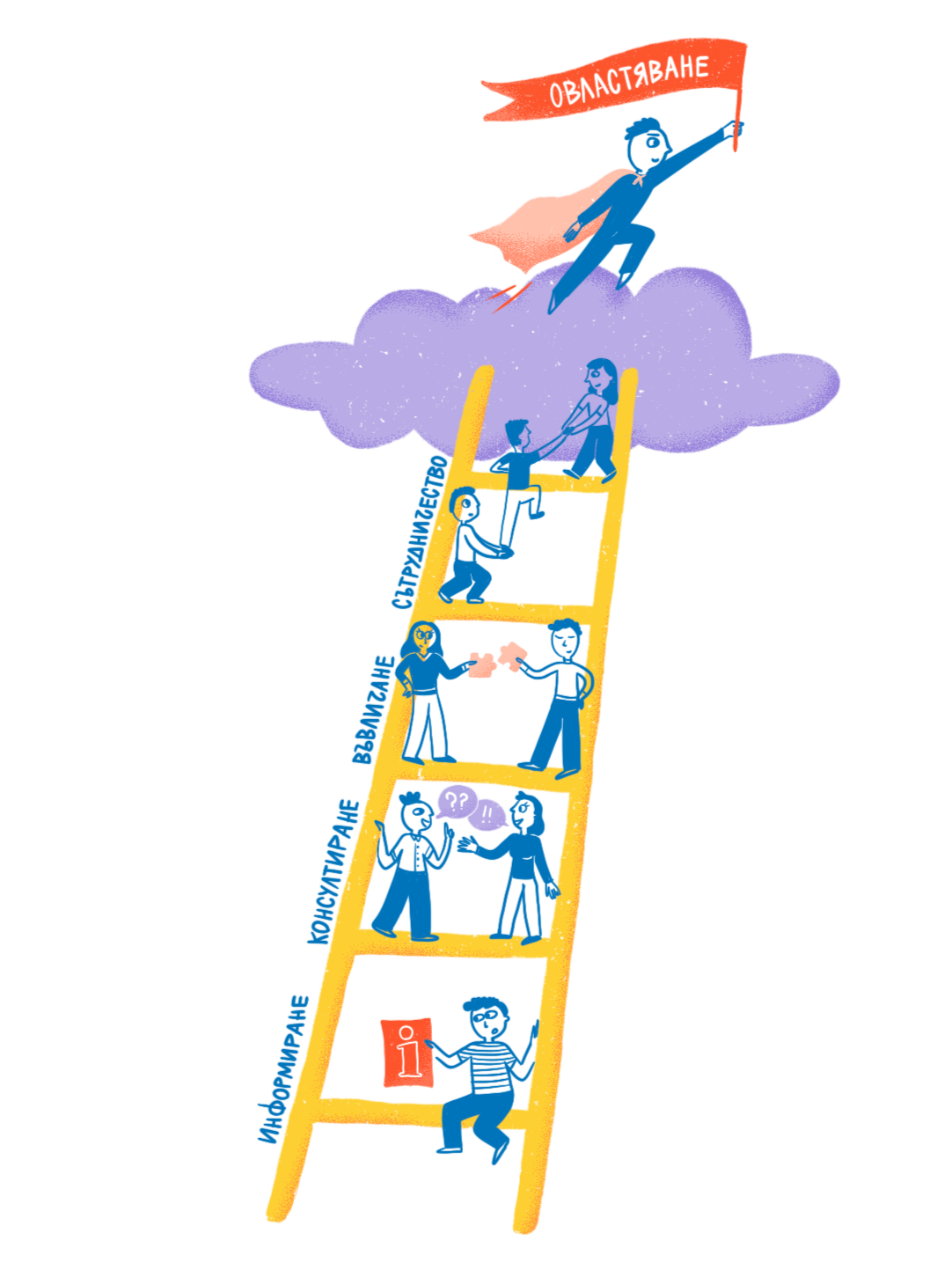

Citizen engagement is most meaningful when it occurs at the problem definition and policy formulation stages, allowing citizens to become more involved in policy development, more committed, and more willing to accept changes that directly affect their interests in the short term.

-

Citizens have the desire and energy to be involved in decision-making processes, but there is a need for a facilitated process and trust building. The process takes time and needs to be prepared systematically, not with ad hoc activities. The participation of representatives of the local administration in the different stages is key so that citizens can recognize them as partners with whom they can jointly discuss and change the environment.

-

Building constructive relationships with citizens is also an investment for future processes and changes. It also improves the environment for dialogue and trust between citizens and institutions in the long term.

-

New ideas are born at the intersections of experience, expertise and perspectives. To achieve this, public discussions and meetings need to be organized in a way that attracts citizens of diverse ages, social status and opinions. There is a need for different formats and channels of communication and engagement to reach the largest number and most diverse groups, as well as good structuring and moderation of the meetings.

-

Often, public discussions are limited to forming camps “for” and “against” a given solution. This polarizes instead of opening up space for creating new solutions. An example on how to deal with this from our work is the use of a more open question - “How would we like to organize parking in the area to live together better?”, instead of the standard “For or against a green zone?”. Thus, despite some tension on the hot topic of introducing a paid zone, the discussions also focused on other topics that are important to citizens and, accordingly, a field is created for innovative solutions. Many of the opponents of a green zone, for example, support the idea of functional zones.

-

Before planning and implementing major changes, it would be more effective to provide the opportunity to introduce pilot interventions with measurable results and feedback in order to objectively assess their effect. In this way, we can verify the effect of the planned change in a low-risk manner, but also its perception by the affected parties through real testing of the changes, rather than theoretically. In this way, solutions adapted to the local context and tailored to the specifics of the regions can be created.